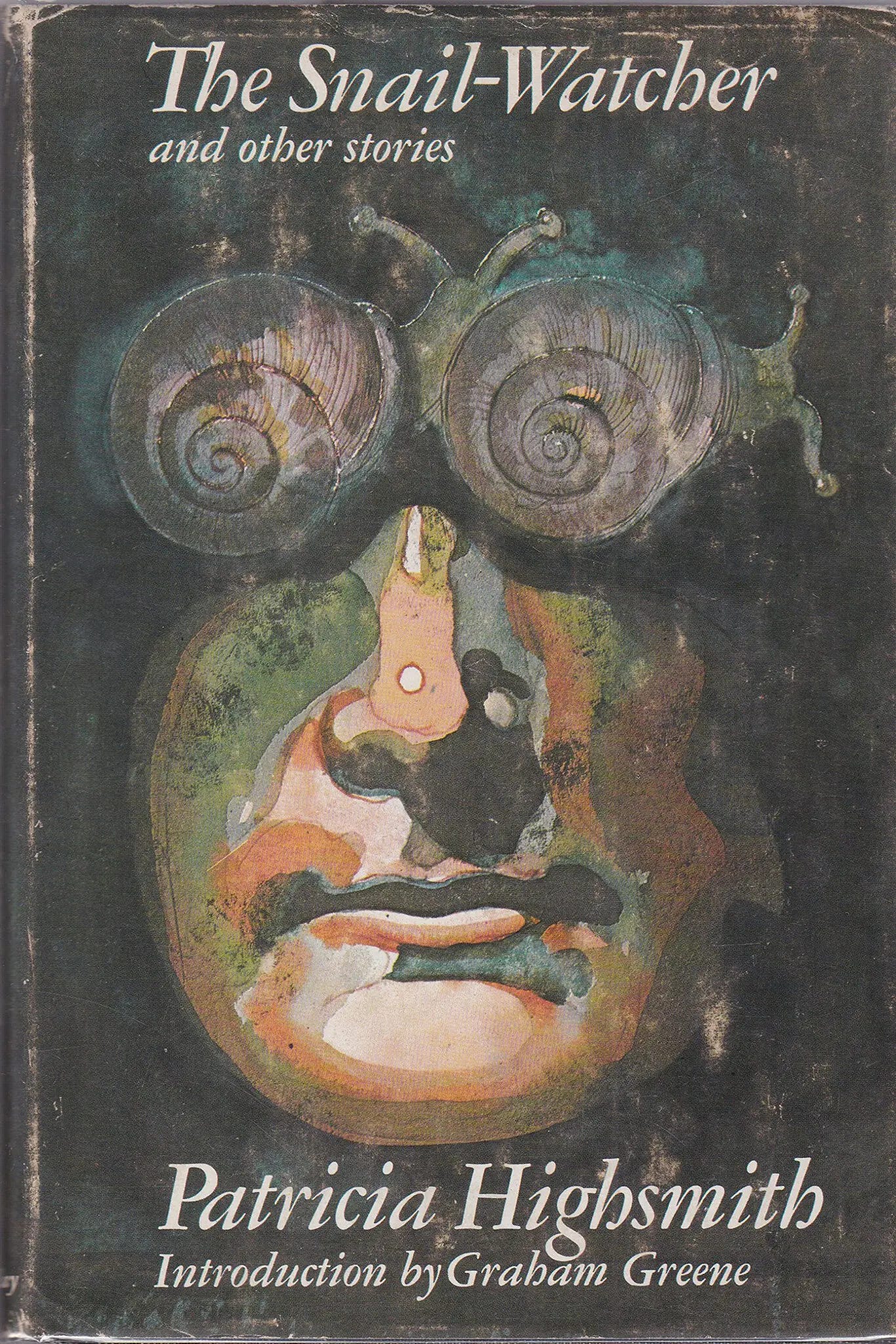

On Patricia Highsmith’s snails & discomfort

Slimy pets the author loved enough to carry around in her handbag and feature in her short story “The Snail Watcher” were deemed by her agent “too repellent”

*spoilers alert*

*slithery snail horror alert*

I’m currently revising a short story called “Vermin”. As I seriously ponder the breeding cycles of household mice over breakfast and scroll past disturbing facts about the copulation of bed bugs in bed (Ridley Scott’s Alien is basically a non-fiction), I wonder about the boundary of what might be considered to the reader too repellent. Just before the thoughts of sanitising the story start to creep in, I find myself in timely company with Patricia Highsmith’s “The Snail Watcher”.

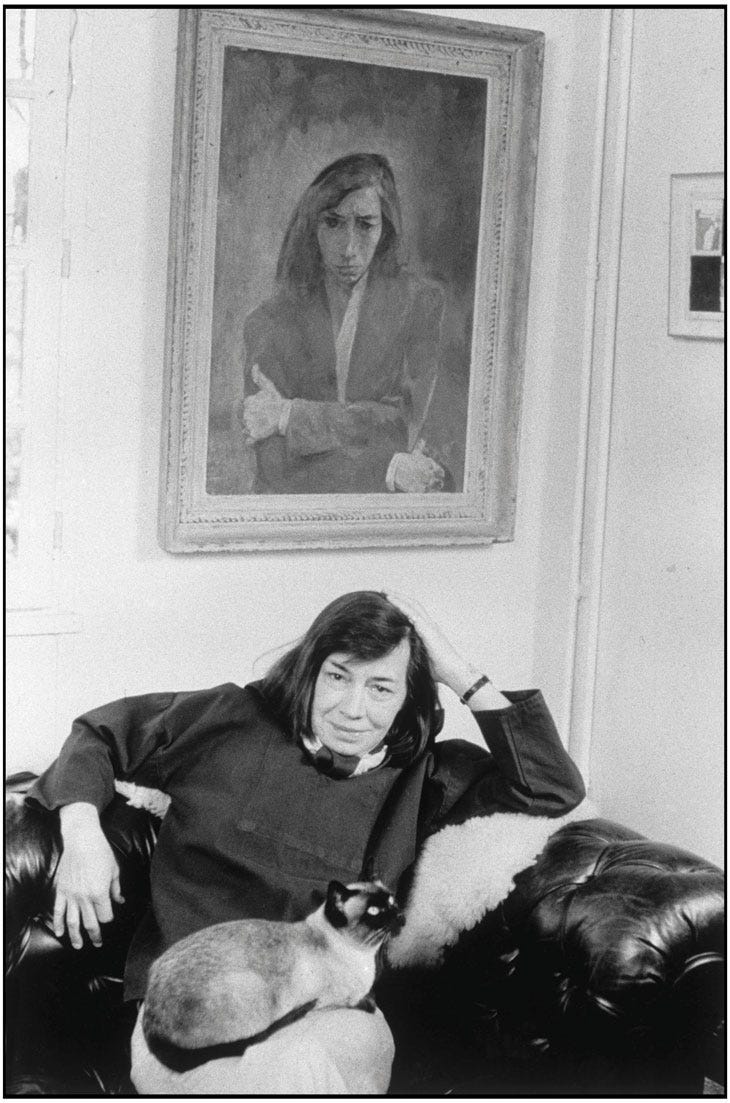

I love Patricia Highsmith. I feel quite at home with her amoral characters who let their obsessions run wild until they consume them. For Tom Ripley, the protagonist of her most well-known novel The Talented Mr. Ripley, desire is at odds with gay repression. As a result, the objects of his fixation, and anyone who stands between them, inevitably, wind up dead. A similar trajectory of events can be observed in Vic Van Allen’s life, a charmingly unhinged, pass-ag protagonist of Deep Water, whose non-conformist pride that allows his wife Melinda to have affairs and publicly humiliate him is also what gets her and her lovers killed. And while the suspenseful lesbian romance classic, The Price of Salt, can hardly be called a crime novel, the stakes of its central subject—romantic obsession—are no less extreme. In the context of the strict social norms governing mid-century femininity (the ‘50s) where homosexuality was considered worse than any kind of heterosexuality, including pedophilia, Highsmith wrote under the pseudonym “Claire Morgan” (in the LRB’s podcast, Terry Castle astutely puts how the act of writing The Price of Salt was more risky than Nabokov’s controversial, and celebrated by a certain kind of man for all the wrong reasons, Lolita). Thus, for the novels’ protagonist Therese, the price of her obsession with the older, wealthy and unhappily married Carol is Carol’s daughter. In light of Carol & Therese’s sexual proclivities, Carol’s jealous, vengeful soon-to-be-ex-husband threatens to put her sanity up for questioning along with her fitness to be a mother.

“The Snail Watcher”’s Peter Knoppert’s fixation is relatively less dramatic. The story begins with Mr Knoppert’s innocent and “vaguely repellent pastime” of breeding snails in his office. Partner in a brokerage firm who had devoted his life to the aggregation of wealth, he is fascinated by how a handful of specimens can multiply into hundreds “in no time”. After becoming transfixed by the snails’ orgiastic mating ritual—“their faces came together in a kiss of voluptuous intensity”—Mr Knoppert lets his pets breed freely to their hearts’ content and leaves them in his office unattended. Sadly, none of his friends or family share his enthusiasm, especially not Mrs Knoppert who had once accidentally stepped on a snail that had broken free to slither along the office floor. She has never forgotten the horrible sensation.

Are you repelled yet?

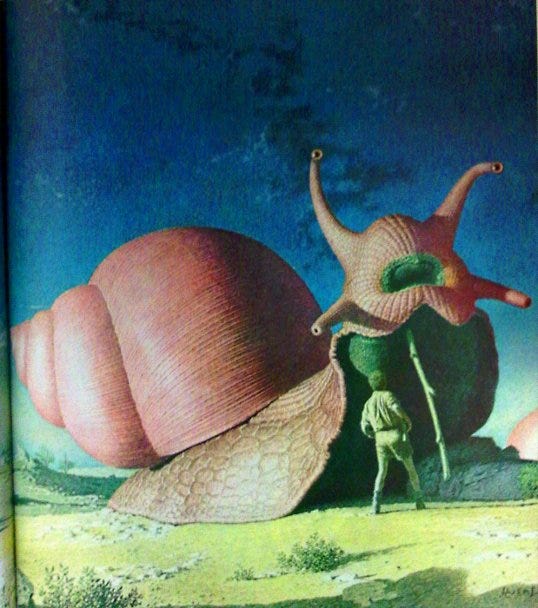

When Mr Knoppert comes back to his office in over two weeks, every surface is “teeming” with snails. The floor is alive and moving with no carpet in sight. The chandelier is a “grotesque clump”. Shocked, Mr Knoppert steadies himself on the back of the office chair and accidentally crushes a mound of snails beneath his hand. Soon, he looses his balance and falls into the gruesome sea of murderous snails, who have already begun crawling up his legs. They block his nostrils, his eyes and his mouth. “Help!” Mr Knoppert cries while choking on a snail, but Mrs Knoppert cannot hear him—the walls are soundproofed with snails.

Yes, I find the plot of “The Snail Watcher” intensely hysterical; yet I cannot deny that it makes my skin crawl. Maybe it’s the description of the chandelier teeming with snails—just that word, teeming—or that part when Mr Knoppert can feel the snail gunk on his tongue. For readers less prone to morbid fascination, the cut-off line might have been when a small tentacle had shot out from one snail and “arched over toward the ear of another” on page two. Or perhaps, like Mrs Knoppert, you’ve had it with the snails right from the first paragraph, at the crunching and squishing sensation she felt underfoot. I don’t know at which point exactly Highsmith’s agent was irked by the snails in 1947, but (according to a Times article) they deemed “The Snail Watcher” too repellent to show to the editors.

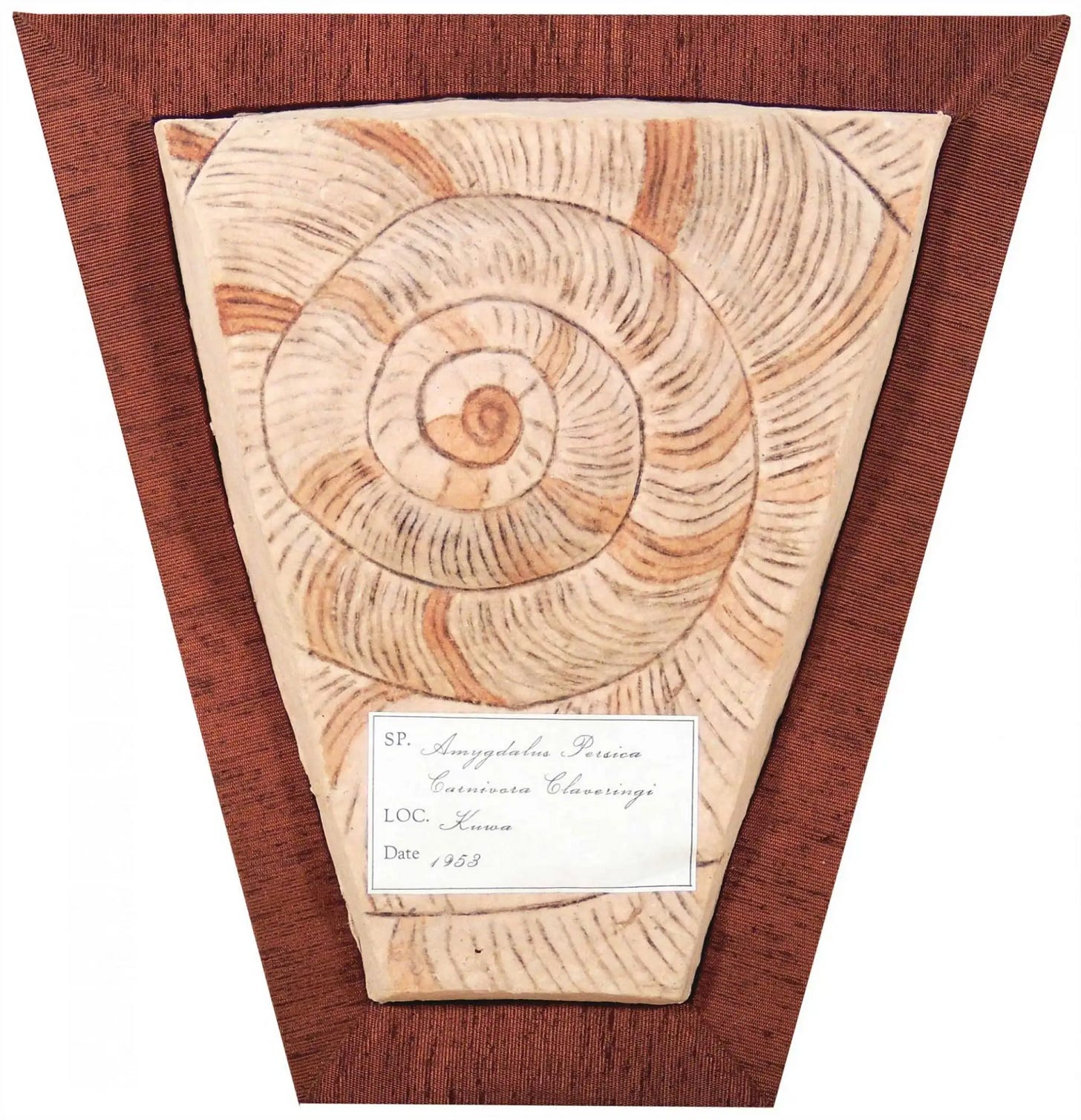

I don’t get it. If I crank the lever on the animal-horror genre, much more horrific things will come sprawling out: the great white shark of The Jaws, poisonous ants, murderous bees, giant spiders, bears, dinosaurs a là Jurassic Park and unstoppable warrior-suicide swallows, sparrows, hawk, larks, starlings and finches of Daphne du Maurier’s “The Birds”. But snails? And not the giant exotic snails of Highsmith’s other snail story, “The Quest for the ‘Blank Claveringi’”, but ordinary snails you might find cooked with garlic butter and white wine, or accidentally step on on the pavement after a rainy hour. To me, this particular strain of monster is terrifying because of its unassuming, domestic nature—a scare like a gentle tentacle recoil, at first; then, gasping for air—pleasurably morbid down to the last word. I want to read (and write) more things in this verve.

On the other hand, if Mr Knoppert’s office was filled with cockroaches, not snails, could I enjoy the story in the same way? Having grown up in a suburban Moscow apartment block, I can tell you right now that cockroach-in-mouth as climax of the story would have been too real. Pet snails? Yes. Cockroaches? No thanks.

But let’s stay with snails for now. Teeming chandelier, snail on tongue. What’s doing it for you? The slithery texture sucking the skin all over and suffocating breath, or the sheer psychological overwhelm seeing the snails in great numbers, never quite knowing where one begins and another ends? Whatever tickles your senses, let us focus on the repulsive sensation. I experience it as a sort of clenching, neck tendons and pelvic floor, shoulders to ears and—you guessed it—a falling sensation in the stomach. It’s a much milder kind to the falling I get on airplanes or when I watch Hitchcock’s Vertigo—Highsmith’s snails, even at their extreme, don’t lose the comedy. You might disagree. You might pick height over creepy crawlies. Maybe you are an adrenaline junkie, plunging yourself regularly down a cliff or a waterfall with or without a rope, and can watch Alex Honnold climb rock-faces free solo in person without so much as letting out an eesh. Maybe you are a neat freak at home—God forbid your socks aren’t paired and organised in the drawer by day of the week—but when it comes to the three/ten/thirty second rule, you’re chillin’. Apple rolled onto the Subway floor? It’s ok, just blow on it a bit.

It’s okay. We are all different, you unhinged maniac.

In short, it boils down to your particular flavour of voluntary discomfort. Personally, I love psychological suspense. Yes, I’m partial to blood and guts, but I’m not much of a Saw fan; I find the crushing social awkwardness of The Talented Mr. Ripley much more suspenseful and heaps worse than a sawed off limb, yet my cringe-factor won’t allow me to sit though a season of Peep Show. Maybe it’s something about its nauseating camera-work, or maybe it’s the nature of its depressing relatability vis-à-vis my need for escape when I watch TV. Rape scenes are a number one repellant for me in films—I can read, but I won’t watch—and although I have sat through some quality films with rape scenes in them, it’s a very nuanced balancing act for the director to do them justice, and even then I probably have to skip. (Narcos is a TV show that does it badly, I hate it with a passion for many reasons, hope it burns in hell).

As a serial capturer of grasshoppers in childhood and a previous proud owner of two pet rats, snails rouse curiosity. Mr Knoppert and Highsmith’s affection for the weird creatures feels kindred. Sweet. Admirable, ableit this affection leads the snails to multiply beyond control and turn murderous. But still, they find curiosity in what others do not. Mr Knoppert claims that “the snails have opened my eyes to the beauty of the animal word”, not to mention Highsmith’s description of snail sex of anatomical accuracy remarked upon by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. What’s more, Mr Knoppert feels himself superior to his peers with more pedestrian tastes who see snails as only fit for eating. “Did you see anything like this?” Mr. Knoppert tells the cook, enchanted by the little creatures’ sexual activity, their “earlike excrescences” precisely “rim to rim”. The cook is indifferent. “No. They must be fighting,” they say and walk away.

So, who do you relate to most? Mr. Knoppert, the man with a snail enthusiasm that got him killed; the indifferent cook; or the cautious Mrs Knoppert who saw the disaster coming the moment she crushed the first shell?

I know who I relate to…

Custom to the protagonists of most horror stories, it’s Mr. Knoppert’s unhealthy curiosity that makes him the perfect victim. He ignores all signs of danger: the body’s instinct to recoil, his wife’s multiple warnings. What I find particularly interesting is that he doesn’t only keep snails, but lets them breed without supervision in his office. And he does this in spite of his peers’ aversion. He loves to feel different! “The fact that no one, at least no one that he knew of, was acquainted with a fraction of what he knew, lent his knowledge a thrill of discovery, the piquancy of the esoteric. Mr Knoppert made notes on successive matings and egg hatchings. He narrated snail biology to fascinated, more often shocked friends and guests, until his wife squirmed with embarrassment.” Since I’ve interviewed two men who’ve worked in the pest-control services, this quote speaks volumes to me. I never could shake off the avid fascination with their shocking anecdotes, or forget the sparkle in their eyes as they recounted the stories, I do not doubt, for the trillionth time. I saw them immediately as snake charmers, magicians, people who have been in the vermin-filled trenches of humanity, peaking into our basements, under floorboards, behind fridges and under beds—places where any horror fan will tell you to never, ever look.

(“Don’t look now,” the husband tells his wife in the opening line of Daphne du Maurier’s masterful short story under the same title. And what does she do? Of course, she looks.)

Patricia Highsmith is that kind of magician. She dares and she looks. She obsesses, despite her better judgement. She liberates the snails just to see how their lascivious breeding might end. Need I add that the author was a proud owner of pet snails? According to the Times article, she was known to bring to a party a lettuce head covered with pet snails in her handbag and after being told that it was illegal to bring live insects into England from America, smuggled them under her breasts. (I’m aware of writers’ tendency to self-mythologise, but want this badly to be true, so it is). Oh, and in Deep Water Vic has a terrarium with two pets—want to guess what kind? At one point in the novel, when things are spinning blissfully out of control, Vic watches his pet snails longingly as they lock into a slithery, lustful kiss: a stand in for the kind of passion him and his wife Melinda have not shared in years.

Admit it, it is a little sexy.

I am, too, transfixed by “The Snail Watcher”. Why? I’m not sure. Maybe, like Knoppert, Vic and Highsmith herself, I’m gleeful with my own superiority, with my willingness to prod at the boundaries of what feels comfortable and even invert the sensation, make disgust feel like heavenly pleasure, or maybe just pretend that it does. Or maybe, like the willing subjects of horror films, my instinct is to move in the opposite direction of don’t, until it’s too late.

Until then, long live Patricia Highsmith’s snails!